Are your people working with you or against you?

Weâll give you the answer right here so you can decide if reading this post is worth your time.

The key to being a great leader is how you share power and responsibility amongst the leader and followers. Leaders who donât share responsibility for leading and power with their followers often experience stress, burn-out and less than satisfactory results. The answer is not to attempt more controls.

Consider this idea before you move on: would you follow you into a burning building and trust you would get out alive? In this case the leader and the followers both have responsibilities and the power of choice: to say yes or no to follow and if the answer is yes, to provide information and useful assistance in the moment itâs needed.

For that to work well for all involved, everyone must know how to lead and follow in any given moment. A leader canât be the hero to everyone.

This was the epiphany and hard won experience of the US Military Academy as they cast a long hard look at previous battles at what happens to soldiers in the field who suddenly donât have their leader or have lost contact. In studying what occurred in those situations, the horrific reality was that soldiers who did not know how to lead themselves or how to follow effectively and take on or let go of the leadership mantle when needed, didnât survive. And even more telling, their leaders, attempting to carry all the responsibility and all the power, did not fare well either.

Itâs a myth that leaders who accomplish great things get there on their own skills and expertise.

Itâs also a myth that leaders are born, not made.

And letâs add to our myth list one more element: the idea that command and control style of leadership is the only one that gets the job done.

Long before it was popular or even proven, the US Military Academy started developing the concepts of Followership.

Leaders who have Followership Intelligence (FQ) have more than a rapport with their teams: they know they can count on each other so the weight of success is shared across all the team, not just the leader. In action, organizations who have leaders with FQ receive more than just compliance, more than just productivity. Organizations receive and followers contribute their best selves in a way that ordinary leaders rarely inspire.

In 2006, The Gallup Leadership Institute, part an initiative of the University of Nebraska and The Gallup Organization, hosted the first summit on the little known factors that contribute to effective leadership. Followership was on the agenda, and Rob McGregor, president of Spirit West Management, was invited to present his theories on what contributes to Followership Intelligence â the ability to step in and provide what is needed in the moment for a leader and even lead when needed to deliver an effective result. Imagine as a leader, stepping aside for one of your reports to lead because he or she is the better choice in that moment.

As a result of that Summit, Rob was invited to test his theories, working alongside Ph.Ds Melissa Carsten, Mary Uhl-Bien, Bradley West and Jamie Patera. They survey organizations in the US and Canada to find out if FQ existed. Their qualitative research proved that there are people in every organization that naturally have FQ and if it was taught more leaders would achieve more reliable success. The Leadership Quaterly 21 (2010) pp 543-562 published their study âExploring Social Constructions of Followership: A Qualitative Studyâ

To learn more about how you can add Followership Intelligence into your leadership toolbox, read the breakdown of the elements that were proven in the study, below.

Since this first study, Rob has taught FQ to corporate leaders and managers as well as to police organizations where split second decision making requires the sharing of information and power. To have him speak at your event, and bring Followership into the leadership of your organization, please call 604-377-4307. Rob is a Ph.D candidate at the University of Lulea in Sweden pursuing an in depth study of how to apply Followership to sales teams to determine how FQ might affect sales results.

Leading in a way that others can followFQ: Followership Intelligence

By Rob McGregor with Lorraine McGregor

Abstract

The concept and practice of Followership Intelligence (FQ) holds that leaders must lead in a way that followers can follow and that followers contribute to the process of leadership through agreeing to follow those leaders. FQ shifts the idea that leadership is a behavioural phenomenon. It also extends beyond the idea that for effective leadership, people must learn to be good followers. FQ is a critical element that must be explored through observation and discussion in order to further the study of leadership.

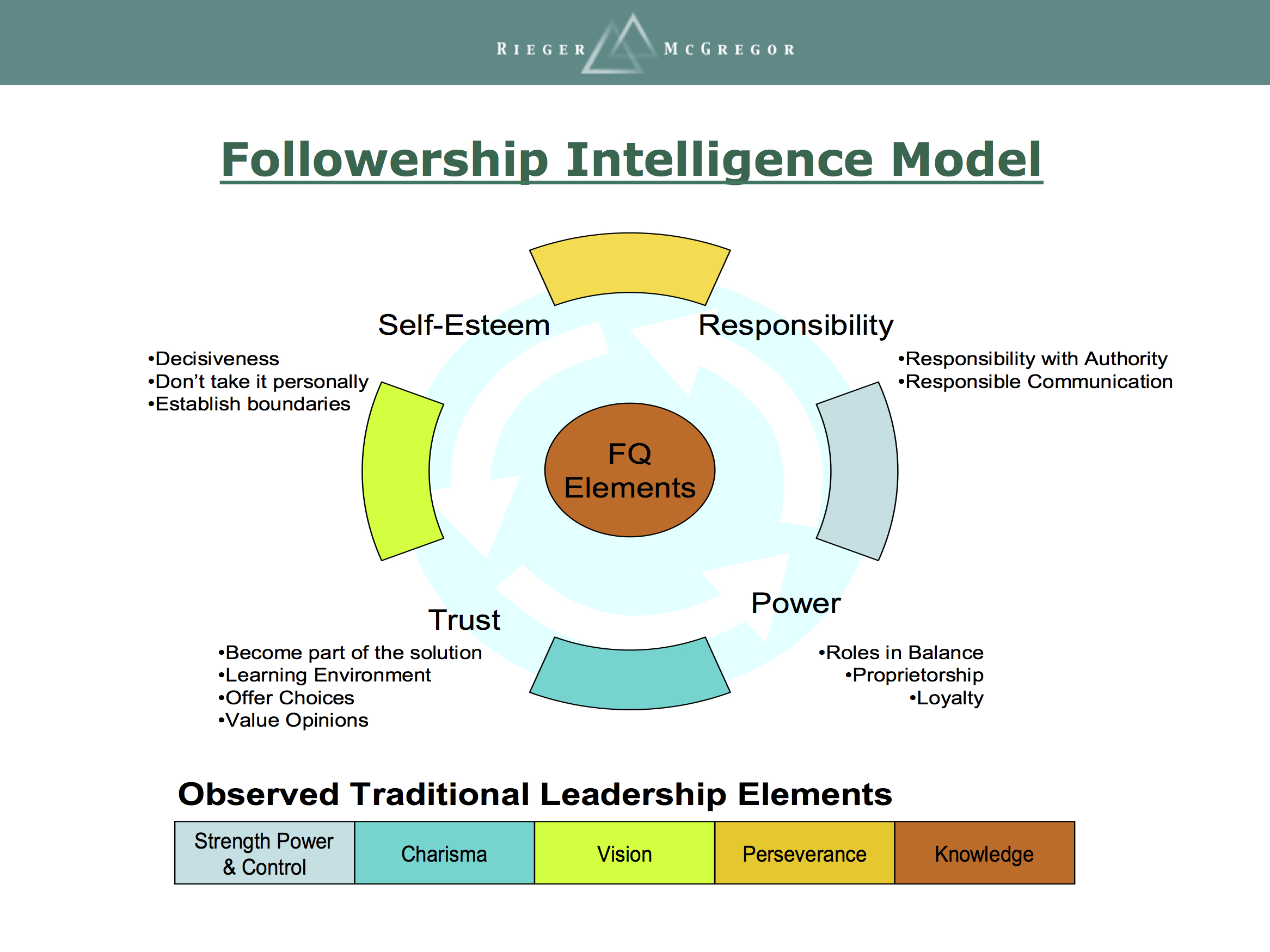

FQ leadership is a shared responsibility between leaders and followers that is held in balance by the mutual recognition that both sides hold power. Having FQ encompasses managing personal power, responsibility, trust and self-esteem so that they are embodied by all parties. This requires a shift in understanding and application that is foundational to the concept of FQ. The promise of FQ is that because there is mutual contribution and greater buy-in, creativity and productivity result and so deliver greater shareholder value. Observation suggests there is a core skill set that, when present in a leader, inspires followers to move beyond compliance.

FQ leadership is a shared responsibility between leaders and followers that is held in balance by the mutual recognition that both sides hold power. Having FQ encompasses managing personal power, responsibility, trust and self-esteem so that they are embodied by all parties. This requires a shift in understanding and application that is foundational to the concept of FQ. The promise of FQ is that because there is mutual contribution and greater buy-in, creativity and productivity result and so deliver greater shareholder value. Observation suggests there is a core skill set that, when present in a leader, inspires followers to move beyond compliance.

The FQ skill set has four core elements that are described in order to give a starting point for research. These skill sets are the operational embodiment of FQ.

This concept is laid out in order to open the discussion to further the study of leadership. Empirical research is required to test the theory and observation presented here.

Introduction

The concept âpeople need to be led in a way they can followâ originated with Moses Coady (Schugurensky 2001) a Canadian Adult educator, priest and the founder of the Antigonish Society.

Coady observed that: true leaders are adult educators; people do not change just because a leader wants them to; and people do not change in the direction that is most beneficial to the organization. Coady believed that followers had to recognize their power and their responsibility in the role of followers, and leaders had to recognize their role in inspiring followers to want to follow for change and momentum to occur. These concepts form the basis on which I have built Followership Intelligence (FQ).

Context in Leadership/Followership Literature

Leadership literature is populated with many variations and distinctions as to what makes an exceptional leader. Only recently have discussions emerged about the role of followers and how leaders can hone followership skills (Wallington 2003). There is a gap between what is discussed in theory and what occurs in practice. FQ, my descriptor for what I have observed in practice and have analyzed through my work with leaders and followers, will bridge this gap. I have attempted to define the critical skills that enable some leaders to inspire followers.

Followership can and does inform the effectiveness of leadership. There is an explicit and implicit relationship between leaders and followers that has yet, perhaps, to be fully explored in leadership literature. My hypothesis is that a leader who understands this interdependent relationship may be said to have FQ. The leader and follower each have certain responsibilities that are critical to successful outcomes. Both follower and leader have areas of responsibility to attend to in order for high performance and productive action to emerge from a leader-follower relationship. Specifically, a leader has the responsibility to deploy effectively the assets and resources paid for by an organization in order to maximize shareholder value. One of those assets is the human capital â the followers. A leader who fails to inspire followers to bring their most productive attention to the tasks at hand is not making optimum use of these resources

Correspondingly, a follower has a duty to exercise their best effort in doing the work of the organization. Following responsibly is part of the employment pact. The reader may note the obvious Catch 22 in this situation: should the leader fail to inspire the follower, the non-FQ follower can blame the leader for his/her lack of appropriate leadership and the non-FQ leader can blame the uncooperative followers. When neither group takes responsibility, blame is the result. Blame affects the culture and ultimately impairs the productivity of the employees, reducing the return on human capital assets. A culture that uses or condones blame is one where leaders and managers lack FQ. People drive the business activity. The lack of FQ on the part of the leaders and the followers and the failure to engage it in this dynamic creates a culture that reduces drive, profits and employee performance.

Correspondingly, a follower has a duty to exercise their best effort in doing the work of the organization. Following responsibly is part of the employment pact. The reader may note the obvious Catch 22 in this situation: should the leader fail to inspire the follower, the non-FQ follower can blame the leader for his/her lack of appropriate leadership and the non-FQ leader can blame the uncooperative followers. When neither group takes responsibility, blame is the result. Blame affects the culture and ultimately impairs the productivity of the employees, reducing the return on human capital assets. A culture that uses or condones blame is one where leaders and managers lack FQ. People drive the business activity. The lack of FQ on the part of the leaders and the followers and the failure to engage it in this dynamic creates a culture that reduces drive, profits and employee performance.

The concept of followership has also been associated with servant leadership. To be clear, FQ does not require the leader to be a servant to the followers. In practice, servant leadership can appear to minimize the interdependencies between follower and leader and so place the responsibility on the leader to serve the follower. The follower is free to respond as they choose and this can open the door to misuse this freedom and be justified in that misuse.

On the opposite side of the spectrum, a leader that expects obedience is ignoring their responsibilities to facilitate the full deployment of followersâ resources. Much of the study of leadership has approached it as a behavioural phenomenon: that is that leadership is a function of the individual in the leadership role and is therefore more of a behavioural skill that varies dramatically from person to person in how it is actually practiced. While that may be true, this is only a piece of the picture of leadership, and most importantly, not the beginning point for effective leadership.

Conventional wisdom has suggested that the one with the power is the leader, and that followers obey this power. What I have discovered is that a follower has a great deal of power, perhaps even more than the leader in some situations. However, this power often goes unrecognized by the follower and ignored or competed with by the leader. A leader with FQ understands and works with the power of the followers which is then rewarded with buy-in or full participation versus marginal compliance. Non-FQ leaders in similar situations may experience resistance, or at best compliance and are baffled. For leaders with FQ, accessing buy-in is a natural part of how they lead.

The Followership Intelligence Model

My hypothesis suggests there are four elements involved in FQ which span what I observe as the traditional view of leadership as seen in Figure 1 below. Within each element are distinguishing behaviours that when practiced, fully express the FQ element and inform and link to the next element in an integrated and cohesive manner. Each element enriches the next element in an interconnected flow which breeds the âintelligenceâ quotient for followership.

Can these skills, attitudes and behavioural approaches be learned? Certainly, they can be studied and habits consciously can be changed. However it is too early in the understanding of this leadership dynamic to determine whether FQ is an innate ability or a set of principles that can be learned through conscious and intentional effort and integration.

The following is offered to begin the dialog on the topic of FQ and as seed for future research in this field in hopes that others can add value. Only then can we assess whether FQ exists and is learnable.

Figure 1 â The FQ Elements

-

Power

Understanding power is the key to FQ. Internal (personal) power is life energy. External power is generally seen as control, but control is a myth. External power is simply a collection of internal powers, which at most we can only have influence over. People always retain their own internal power to choose to be influenced or not. External power and internal power are often confused. People crave and pursue external power but I suggest it is internal power they really need and desire. People attempt to acquire external power, thinking it will refuel their life energy and expand their sense of internal power, so they can feel more in control and feel better about themselves: another myth. Internal power exists within our self-perception. It canât be acquired, only acknowledged by the self, and that is what increases it.

External power has been commoditized through societal misunderstanding (conventional wisdom still teaches people that power and control are irrevocably coupled, even synonymous). Conventional wisdom also suggests that internal power can be bought, traded and stolen. This too is a myth and therein lies the root of the leadership problem and is often the source of conflict in organizations. The polarized thinking and blame that grows from conflict is the result of people attempting to acquire personal power from external sources. FQ leaders recognize they have personal power and use this effectively, rather than attempting to replace it by pursuing external power (the difference between having authority and being authoritative). They refrain from thinking it can be depleted. An FQ leader knows that everyone retains personal power and choice even if in the moment they feel powerless. They become skilled at helping their followers find and engage their power again

External power has been commoditized through societal misunderstanding (conventional wisdom still teaches people that power and control are irrevocably coupled, even synonymous). Conventional wisdom also suggests that internal power can be bought, traded and stolen. This too is a myth and therein lies the root of the leadership problem and is often the source of conflict in organizations. The polarized thinking and blame that grows from conflict is the result of people attempting to acquire personal power from external sources. FQ leaders recognize they have personal power and use this effectively, rather than attempting to replace it by pursuing external power (the difference between having authority and being authoritative). They refrain from thinking it can be depleted. An FQ leader knows that everyone retains personal power and choice even if in the moment they feel powerless. They become skilled at helping their followers find and engage their power again

Further, the FQ leader sees external power as only the collection of the internal powers of people involved in the structure. Without the individuals of the collective there is no external power. Therefore external power is not a commodity. Each person within the collective has more than enough personal power to choose to follow someone and still maintain their own power. And so it follows that each person needs to self manage their personal power in order to be an effective leader or follower.

It is the power of the agreement to follow that allows the leader to lead that makes effective leadership possible. The FQ leader respects the followersâ internal power and creates appropriate opportunities for the followers to buy-in to the leaderâs vision. The followers respect the internal power of the leader and allow the leader (in essence give permission) to coordinate and direct (influence) their collective power. Because an organization is only as strong as its human capital assets, this permission sets the atmosphere for buy-in, which then increases the collective internal power and performance of the group and so in turn maximizes shareholder value. Shareholder value then becomes a shared responsibility.

Roles in Balance

Roles and responsibilities are the guidelines for balancing power. They are vital for productivity, performance measurement and acknowledgement of effort. They also ensure that the right talents are assigned to the right job. The FQ leader is able to help each person to understand their role, their contribution and how they fit in the big picture. The FQ leader mentors (influences as opposed to directs) people to embody the power inherent in that role as it applies to fulfilling the goals of the organization and the personal needs of the individual.

Proprietorship

It is a vital human need for people to feel they are part of something bigger than just themselves. Affinity plays a dominant role in gaining informal power and buy-in. The FQ leader sets the atmosphere for people to value their contribution which then delivers this sense of proprietorship over the organizationâs values and achievements.

Loyalty

An FQ organization engenders loyalty in two ways: the leaders are able to listen in a way that signals to followers they are being heard; and the leaders are able to speak in a way that followers can understand. When followers are listened to they feel valued and reward the listener with loyalty.

-

Responsibility

Responsibility is one of the most manipulated and maligned concepts in the world of leadership. The search for the âresponsible partyâ becomes an exercise in blame. Making blame the punishment for responsibility does little to engender productive self-responsibility. Blame decreases followersâ willingness to take risks and consumes leadersâ time. Both acts curb creativity.

In order to move the concept of responsibility back into a useful realm, an FQ leader deconstructs the situation to discover how the result was achieved. This is a neutral fact finding mission to gather âlessons learnedâ on all types of projects regardless of outcomes. This normalizes the process of looking back in order to learn, rather than find fault, and removes the element of blame. The leader sets an atmosphere that is driven by learning rather than scapegoating. With this shift, all involved feel safe to look at their efforts and see the pros and cons of that contribution in order to be able adjust inputs or to reproduce the result when required. In turn, it also clearly identifies performance improvement opportunities.

In order to move the concept of responsibility back into a useful realm, an FQ leader deconstructs the situation to discover how the result was achieved. This is a neutral fact finding mission to gather âlessons learnedâ on all types of projects regardless of outcomes. This normalizes the process of looking back in order to learn, rather than find fault, and removes the element of blame. The leader sets an atmosphere that is driven by learning rather than scapegoating. With this shift, all involved feel safe to look at their efforts and see the pros and cons of that contribution in order to be able adjust inputs or to reproduce the result when required. In turn, it also clearly identifies performance improvement opportunities.

Responsibility with Authority

Responsibility without authority is futile, and authority without responsibility is catastrophic. Without authority, a task becomes a recipe for failure and a breeding ground for blame. Giving authority without the responsibility is inviting reckless risk taking and creates the opportunity for people to hide behind the smoke and mirrors of ambiguity and confusion of roles.

The coupling of responsibility with authority really is the concept of accountability. In an FQ environment, accountability replaces blame. Accountability is respecting that each person is responsible for their contribution, and so negates the opportunity and need for blame

Responsible Communication

An FQ leader or follower can âname the elephant in the roomâ because naming it is not the same as blaming someone for its existence. The âelephantâ is that which everyone sees or senses but no one addresses. This creates a thick atmosphere of denial that makes dialogue less effective. That atmosphere can be laden with non-verbal communication barriers that consume productivity. Naming these barriers is achieved through using neutral observational language, which is the definition of responsible communication. When blame is not an element in the discussion there is no debate about the value of communicating what is being observed.

-

Trust

Trust is an important aspect of interpersonal interaction that aids organizational functioning. It is cautiously given and easily revoked. Social convention suggests that it must be earned, and once broken is often un-repairable. The concept of trust is vital; the practice of trust is often problematic. Trust can be used as a weapon that invokes blame and guilt. Irresponsible communication indulges in blame, guilt and shame, which depletes and erodes trust. Leaders need to trust their followers and followers need to trust their leaders. By definition, FQ (leading in a way people can follow) honours that trust relationship. FQ in practice allows for mistakes to be made: The FQ leader and follower are not quick to revoke trust as the mistake is seen in the context of learning. The FQ leader takes the time to explore how something happened and uncovers the specific contributing factors to reveal lessons learned. In order to accomplish this, transparency (being open and honest about motivation and actions) is required. Transparency is a cornerstone that keeps trust alive and meaningful. It helps create consistency and safety that allows leaders and followers to take risks and make better decisions.

Trust is an important aspect of interpersonal interaction that aids organizational functioning. It is cautiously given and easily revoked. Social convention suggests that it must be earned, and once broken is often un-repairable. The concept of trust is vital; the practice of trust is often problematic. Trust can be used as a weapon that invokes blame and guilt. Irresponsible communication indulges in blame, guilt and shame, which depletes and erodes trust. Leaders need to trust their followers and followers need to trust their leaders. By definition, FQ (leading in a way people can follow) honours that trust relationship. FQ in practice allows for mistakes to be made: The FQ leader and follower are not quick to revoke trust as the mistake is seen in the context of learning. The FQ leader takes the time to explore how something happened and uncovers the specific contributing factors to reveal lessons learned. In order to accomplish this, transparency (being open and honest about motivation and actions) is required. Transparency is a cornerstone that keeps trust alive and meaningful. It helps create consistency and safety that allows leaders and followers to take risks and make better decisions.

Become Part of the Solution

FQ leaders set an inclusive atmosphere that allows those that are part of the problem to be part of the solution by contributing meaningfully. This brings the follower out from under the stigma of blame (defensiveness) and into the realm of self-responsibility to make different choices. It is an empowering and vital part of maturing the entire team.

Learning Environment

FQ leaders are mentors, bosses, educators and boundary-setters. They set the atmosphere to encourage meaningful contribution that matures the organization and its people. In order to do so they must constantly challenge peers and followers to improve behaviours, think strategically and understand how and why systems work as they do in order to make meaningful improvements.

Offer Choices

Followers who resist leaders often perceive they have no other choice but to sabotage and be contrary and therefore resistance is their last act of free will. Rather than fighting the resistance, FQ leaders offer choices to bring the resistors back into the fold or help them to find the courage to leave. The FQ leader recognizes the power that choice has in transferring responsibility and all it entails to the resistor.

Value Opinions & Expertise

FQ leaders actively seek opinions and other expertise. Being their own authority, they are open to the contribution made, whether in agreement or challenge. The FQ leader respects that the opinions expressed have meaning to the sender and do not have to be seen as criticisms of the receiver. Valuing all opinions signals that the culture is one of collaboration and reinforces the trust and learning environment.

-

Self-Esteem

FQ leaders understand how to build self-esteem. They acknowledge their own and othersâ efforts and are respectful to all people at all times. They discern their own needs and make proactive choices. They resourcefully act on these choices and follow through. They reflect on how to make improvements through encouraging creativity. All of these activities allow them to give to others without strings attached, and in this way they support the building of self-esteem in others.

Decisiveness

There comes a time when the exploration of ideas, choices, expectations, and possible courses of action comes to an end and decisions must be made. FQ teams are able to make the decision and act. FQ leaders retain final responsibility, and FQ followers are able to accept that and cooperate with it.

Donât Take it Personally

People have opinions about others all the time. To take such comments personally undermines self-esteem. An FQ leader knows that such comments say more about the person offering them than they do about the individual on the receiving end. FQ leaders use such comments to understand the needs and concerns of the follower.

People have opinions about others all the time. To take such comments personally undermines self-esteem. An FQ leader knows that such comments say more about the person offering them than they do about the individual on the receiving end. FQ leaders use such comments to understand the needs and concerns of the follower.

Establish Boundaries

FQ leaders know what they do, and do not want and are able to convey this information in a way that makes sense to followers. If those boundaries are crossed, the leaderâs response is predictable and consistent. By setting such boundaries, the FQ leader signals that boundaries are healthy and smart for effective interaction. In this way, everyone on the team understands their own personal limitations and values and can respect others in the same way.

How FQ Makes a Difference to the Study of Leadership

One of the great leadership debates is whether leaders are born or created and what factor personality plays in being a successful leader. Further research into this area will shed light not only on the personality debate but also bring forward more of the practical âhow toâ skills that people need in order to elevate their interactions to a higher level of functioning. Leading with FQ requires a paradigm shift in how those leadership skills are taught, understood and practiced. People I have observed who exhibit FQ skills have made this shift and appear to be achieving more than their peers.

If the purpose of leadership is to provide organizations with capable leaders who can artfully deploy all assets in pursuit of continuous shareholder returns, then FQ could serve as a methodology to train and mentor leaders into full performance. A leader with FQ displays behavioural and cognitive skills and an attitude that conveys respect for the organizational goals by interacting with its employees as powerful, self-responsible, contributing people.

Organizational change happens at the level of the individual, one person at a time. Leaders who understand this concept set the stage for followers to be inspired and fully engaged in contributing to the change process so that it is sustainable in its benefits to the organization.

Implications of FQ in Research and Practice

In summary, the element of power within the theory of FQ promises a definable return on investment. As leaders draw out followersâ proprietorship and loyalty through a greater awareness of how power operates, the organization will experience greater âprofitabilityâ because time is spent productively rather than in power struggles and blame. Self-motivated performance, increased creativity and curiosity to solve problems and approach challenges in a collaborative and more effective and efficient manner in turn contributes to the sense of proprietorship and loyalty to the organization and to the leader. In essence, the organizational activities become the focus rather than the interpersonal distraction of control and stealing power.

Self-responsibility, when coupled with personal power and trust yields high returns. While competing ideas will always exist, the organization using FQ values accepts differences and embraces the richness of diversity. However, decisions can still be made and progress achieved because no one has to thwart the process intentionally or unintentionally by purporting to be right or making the other wrong. This creates an atmosphere of responsible communication where trust flourishes. Trust allows for buy-in despite the existence of different ideas, because those ideas have been responsibly communicated and received. Buy-in releases creativity which breeds healthy individual and team self-esteem. This is essential for the free flow exchange of ideas that brings change and progress.

Self-responsibility, when coupled with personal power and trust yields high returns. While competing ideas will always exist, the organization using FQ values accepts differences and embraces the richness of diversity. However, decisions can still be made and progress achieved because no one has to thwart the process intentionally or unintentionally by purporting to be right or making the other wrong. This creates an atmosphere of responsible communication where trust flourishes. Trust allows for buy-in despite the existence of different ideas, because those ideas have been responsibly communicated and received. Buy-in releases creativity which breeds healthy individual and team self-esteem. This is essential for the free flow exchange of ideas that brings change and progress.

The understanding of the elements of FQ can be used in negative ways to manipulate unaware followers and leaders. For example, there is an old adage that says, âIf I know more about you than you know about yourself, I can control you.â People abusing FQ skills are highly tuned to others and because they understand the dynamics of power they may use it to their personal advantage.

I have observed that there can be negative reactions when a leader has strong FQ. Others that donât understand FQ see that the FQ leader does not engage in their power games and seems to achieve a higher level of success. The non-FQ leader then may seek to compete, undermine or drag down the effort. This reaction will be vital to explore in first hand research. People employing FQ produce results that are of an order of magnitude greater than non-FQ leaders, and when results achieved are disproportionately distributed across the organization this uneven performance creates weak links in the operational chain. Competitive barriers to communication between departments can arise.

Such results may isolate FQ leaders from their peers as people tend to compare othersâ abilities to their own, find themselves lacking or seek to judge the person who does not play the power game. Non-FQ leaders then resort to attempting to steal power from external sources to re-balance the equation in their favour. This then has a domino effect on the cultural and organizational dynamics, impairing productivity and performance. Popularity contests tend to create âus versus themâ camps as jealousy and resentments grow. Teaching FQ and exposing the futility of power brokering could reduce these crippling dynamics in organizations.

FQ leadership may be innate, it may be something we can all learn or it may be both. It evolves as we learn to manage diversity and change in the workplace rather than maintain rigid standards and protocols. Followership Intelligence may be a new thread of research activity in the leadership debate or simply another obscure subtopic that will remain hidden in our struggle to understand human interactions. Exploration is required to prove or disprove the concept.

FQ as a skill set augments any leadership style and builds on the talents already at work in companies around the world, in government, small and big business and in other human associations. The opportunity to observe others and to apply the elements of FQ while following and leading others, will inform our understanding of leadership, followership and the effect each player has on the individual and the collective.

Bibliography

Goleman, Daniel 2004 What Makes a Leader Published by Harvard Business Review ; Jan 2004, Vol. 82 Issue 1, P82-91, 9p. Cambridge, MA

McNamara, Carter 1999 Guidelines to Understand Literature About Leadership Published by Authenticity Consulting LLC, Minneapolis, MN

Schugurensky, Daniel 2001 A History of Education Published by the Department of Adult Education, Community Development and Counselling Psychology, The Ontario Institute for Studies in Education of the University of Toronto (OISE/UT), Toronto, ON

Wallington, Patricia 2003 After You! Why Leaders Should Hone Followership Skills Published by CIO Magazine May 15, 2003, vol. 16, Iss. 15; pg. 1 Framingham, MA